The Economy Hates Surprises. We Should All Love Energy Efficiency.

The energy efficiency community has always had something of a communications problem. While people look at solar panels and wind turbines and see clean energy possibilities, energy efficiency is invisible and seems boring in contrast. And when efficiency experts talk about how it’s less expensive and should be used to help reduce demand before we worry about changing supply, we suddenly turn into nagging parents telling kids they have to eat their vegetables before they can have dessert.

One of the worst but least obvious communications failures we have is our almost singular focus on how much efficiency can save. It’s an easy trap to fall into, because the whole point of energy efficiency is to save energy after all. Whether your concern is saving money, reducing pollution, or just cutting waste for its own sake, the primary reason for any individual efficiency investment is to save energy.

But, from an economic standpoint, the biggest problem with fossil fuels is not that they cost too much. The real killer is price volatility. And that’s where energy efficiency can really pay off.

Crude and Cruel

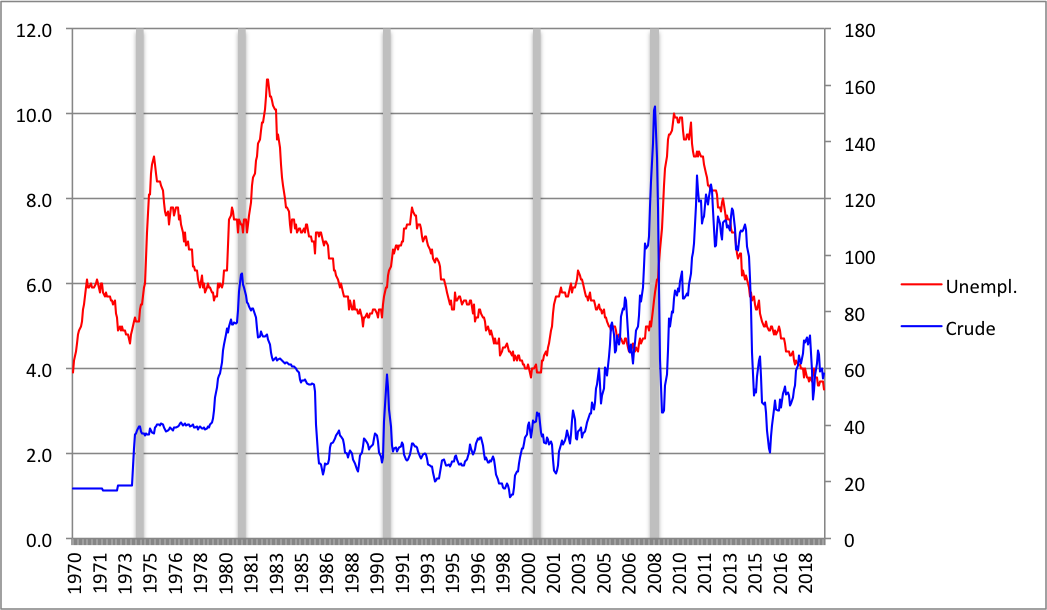

I put together this simple chart showing monthly oil prices (in today’s dollars per barrel, in blue on the right axis) and the overall unemployment rate (in red on the left) with grey bands centered around the exact peak in oil prices. As you can see, every price spike is followed by a spike in the unemployment rate:

This is not a sophisticated statistical analysis, and as everyone knows correlation is not the same as causation. But at the same time, we do know that the oil price shocks of the 1970’s and early 1980’s were in fact major drivers of economic slowdowns. And while we know that the Great Recession of 2008-9 was triggered in large part by a financial crisis that was in turn triggered by a housing crisis, there is credible research out there showing that the housing crisis may well have been triggered by the massive run up in oil prices starting in the early 2000’s and peaking in mid 2008.

The five spikes in the chart, range from 116% in 1990 to 153% in 2000. Not that a doubling of oil prices is a magic threshold, but 100% appears to be the right neighborhood. More modest jumps in the 50% range don’t seem to be enough to really trigger an unemployment event.

One of the most important things to note about this, is that it doesn’t really matter how high or how low oil prices are when the price spike happens, it’s the spike that matters. In the early 70;s and 90’s prices started in the teens and jumped to around $40 per barrel. In the late 70’s and 2000’s they started above $40 and jumped to over $90.

Further, looking at 1974-1978 and again from 2002-2006, it’s clear that even a sustained environment of relatively high prices is consistent with falling unemployment. That is, we don’t need low oil prices to have low unemployment. Avoiding price spikes is the key.

Bacon Makes Everything Better

So where does efficiency come in? What would this chart look like if we plotted some other critical commodity, like bacon? Completely different (have a look). Because as much as we might love bacon, we don’t actually need it. So bacon prices can surge and collapse without having much of an impact on the economy at all. The less dependent we are on something, the less we care about how much it costs.

Which leads to one of the greatest and most under-appreciated benefits of energy efficiency. It can insulate us from the volatility of things like oil markets where price spikes are a regular if unpredictable occurrence.

Debating whether energy efficiency is more or less expensive than the energy it displaces is the wrong question, at least at the macro level. Even if it were more expensive, the fact that its costs are known ahead of time provides incredible value in terms of reduced risk. No smart investor looks only at the price of something before deciding whether it's a good idea or not. The price is meaningless unless they know the risks involved, and the risks of volatility in fossil energy markets can be very high (natural gas might even be worse). Now it just so happens that smart energy efficiency investments do cost less than energy itself, making efficiency a form of insurance that pays you to buy it.

Whether or not energy efficiency saves money depends in large part on whether energy prices are high or low. The reality is that even when oil prices are low, volatility can have significant impacts on the economy, and energy efficiency can help insulate us from its impacts.

This is why when we talk about energy efficiency policy (if not individual investments), the conversation has to be about much more than just cost.

Don’t go there.

And before anyone can suggest that the solution is to produce more oil domestically, bear in mind that the nationality of oil has no relation to its price. American oil producers do not give American oil consumers a discount just because they’re Americans. Increasing oil production anywhere in the world may result in lower overall prices, but the oil market volatility is still driven in large part by geopolitics. If you look at the right tail end of the chart, you’ll notice that oil prices jumped 134% from 2016 to 2018, just as domestic oil production surged by almost 25%.

One last caveat: The only 100%+ oil price spike I didn’t highlight is this last one. Not because it doesn’t hold to the pattern, but because it hasn’t had a chance yet. If it does, and there are always reasons why it might not (like today’s emergency interest rate cut), we should see unemployment heading up again sometime around August 2020.

PS- Just for laughs, here’s what the graph looks like if you shift oil prices ahead by 21 months:

Data Sources:

Unemployment: https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000

Oil prices: https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=PET&s=R0000____3&f=M

Note: Oil prices are only available monthly after 1974. For 1970-1974 I used annual average prices here: https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=pet&s=r0000____3&f=a